Grenada

Legislation and planning process in Grenada

Authors: Charisse Griffith-Charles and Mujeeb Alam.

Links:

- Comparison of legislation and planning frameworks for five countries;

- Local land use planning: example from Grenville area.

- National vulnerability assessment

- Using census data

- Building footprint maps

- Population data

Like many other Caribbean countries, Grenada is also prone to multiple natural hazards, such as hurricanes, storm surges, volcanic eruptions, flooding, landslides, and earthquakes. Additionally, there is risk of Tsunami; as Kick-em-Jenny, an active volcano (erupted about 12 times since 1939) is located about 8 kilometres to the north of the island under the sea at about 180 metres depth. According to the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR, 2010b), approximately 50.1 % of Grenada's population is vulnerable to two or more hazards. Historically, Grenada has been affected by a number of hurricanes which have caused huge economic damage to the country. Hurricane Janet in September 1955 killed 200 people and greatly impacted the agricultural sector. Hurricane Ivan, in 2004, caused approximately US $ 800 million in economic damage (GFDRR, 2010). The hurricane damaged 90 % of the country's housing stock, besides killing 37 persons (World Bank, 2004). Hurricane Emily impacted the southern part of the country in 2005, when the country was still recovering from impacts of Ivan. The country is also affected by tropical storms, leading to flash floods and landslides. As per the EM-DAT (n.d.) database, about US $ 4.7 million in economic damage was recorded in the November 1975 flooding in the country. Heavy rainfall and subsequent flood events in 2011 and 2013 have also affected the country.

Land management in Grenada

The following are the relevant land management and development policy documents in the country.

|

Accepted policies related to land management and development: |

|

|

Draft policies |

|

Relevant Land Management and Development Legislation

|

Relevant Land Management and Development Regulations

|

The Physical Planning and Development Control Act makes provision for preparation of physical development plans as well as monitoring and control procedures. It provides for the performance of EIAs.

The National Parks and Protected Areas Act authorises the Governor General to declare any area a national park as well as authorises the Minister responsible to declare any state owned land as a protected area.

The building code does not make specific provision for construction in areas prone to landslide and flood except for Section 5 Public Health and Safety which specifies at subsection 503.3 that:

No building shall be erected on a site which:

- Cannot be put into such a condition as to prevent any harmful effect to the building or to its occupants by storm or flood waters.

- Has an average site elevation of less than 4 feet above mean sea level.

Landslides are not addressed directly but can be derived from the loading specifications listed at Section 12 of the Code and the soil investigation specifications in Section 13 of the Code.

The National Disaster Management Plan sets out the guiding principles, objectives and operations required to ensure that the country is prepared for disasters and can, through the implementation of the plan minimise loss of life and destruction of property.

Physical planning in Grenada

In Grenada, physical development takes place in accordance with the Physical Planning and Development Control Act 2002 (the Act) (Act, 2002). The Act was approved by the Parliament in September 2002 for the orderly use of land for the public interest. The specific objectives of the Act are to:

- Ensure appropriate and sustainable use of all publicly and privately owned land for the public interest

- Maintain and improve the quality of the physical environment

- Provide for the orderly sub-division of land and the provision of infrastructure and other services

- Maintain and improve the standard of building construction in order to secure human health and safety

- Protect and conserve the natural and cultural heritage

The Planning and Development Authority (PDA/Authority) is the responsible entity in the country for all physical development related activities. It is a statutory body established in accordance with Part II, Section 6 of the Act 2002. It comprises 11 members from government ministries/departments and private sector as suggested in the Act. The role of PDA is to ensure the implementation of the stated objectives set out in the Act. Therefore, the task is to guide the future development of land through physical development planning initiatives at national, regional and local level and to ensure orderly and progressive development of land by introducing development planning policies. The Physical Planning Unit (PPU) is the administrative arm of the PDA and as per the Act, the Head of the unit is the Chief Executive Officer of the authority. The Head is responsible for carrying out the general policy of the Authority. The planning unit has broadly two functions; development planning (setting out the vision of how a region should be developed) and development control (through regulations, standards and other regulatory instruments guide development undertakings in the country).

The Act, makes the provision of the preparation of a physical plan for the whole country. Plans may also be prepared for specific regions or smaller parts of the country i.e. regional and local plans. The plan should set-out prescriptions for the use of land. The plan should allocate land for conservation, use, and development for agriculture, residential, industrial, commercial, tourism, or other specific purposes identified through a consultative process. The plan should also make provision for the development of infrastructure, public buildings, open spaces and other public sector investment works needed for the steady economic growth of the country. The plan must be prepared through an integrated planning process, ensuring its publicity in the course of its preparation. The plan must be approved by the Parliament for its enforcement. The plan remains in effect until rescinded by the concerned Minister. Nonetheless, it is important that the physical plan undergoes a review process after 5 years of its approval for any possible changes and improvements. Once the plan is approved, it is considered to be the principal document to be consulted while making any development decisions for the area with which the physical plan is concerned. The National Physical Development Plan (NPDP) has been prepared for the entire country for a period of 2003-2021. The purpose of this plan is to provide an integrated and coherent framework to promote and guide development activity in Grenada in a sustainable manner. Emerging out of the national physical development plan, a few local area development plans have also been produced, including most importantly, the Greater Grenville development plan.

As indicated, PDA is the only body authorised to determine applications submitted to the PPU, seeking approval for any kind of physical development work in the country. The Authority reviews applications and makes decisions. The Planning Act, clearly states that no person is allowed to start any development work without prior approval of the Authority. Under Part IV, Section 19(1), it is stated that "Notwithstanding any other law to the contrary, but subject to Section 21, no person may commence or carry out the development of any land in Grenada without the prior written permission of the Authority". Therefore, it is mandatory for all persons to get written approval of the PDA for commencing any kind of physical development work in a particular area. The nature and type of development work for which written approval is required has been defined in the Act. However, there are minor development works for which no permission is needed and which could be done without consultation with the Authority.

An application for permission to initiate development work must be submitted to the PDA through the PPU. The application is submitted through a prescribed form called "Application for Permission to Develop Land" together with other specified documentation such as a set of drawings (e.g. site plan, floor & roof plans, foundation, elevation, structural drawings etc), location map etc. Moreover, depending on the nature of the land development, the authority may ask additional documentation and set of information such as topographic surveys, Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) etc. Once an application is formally submitted to the planning unit, it undergoes a review process. The respective technical staff at the PPU and other concerned government departments examine different aspects of the development. For example, a structural engineer checks details related to structure of the proposed development, such as, foundation, beams, construction material, retaining walls, alteration topography, and roof. The Development Control Officer (DCO) specifically visits the proposed site area for evaluating and completing the prescribed observation form. The DCO then reviews different drawings such as the surveyor's plan, location plan, site plan, elevation, architectural details, and electrical and plumbing layouts submitted by the applicant. Finally, the Public Health Officer (PHO) examines issues related to public health; including solid and liquid waste disposal, on-site drainage, and ventilation of toilets and kitchen. The assessment findings are recorded in the prescribed form and attached to the application.

Once an application undergoes a thorough technical review stage, it is then forwarded to the Authority for its review and determination of application. As per law (i.e. the Act), all land and development related applications have to be approved by this Authority. The members of the Authority meet every month or arrange special meetings to review applications. In the meeting the Authority decides whether an application is approved (fully approved), conditionally approved (approved with some conditions to be met), deferred, or refused. Once an application has been reviewed and decided upon, the Authority writes to the applicant and formally informs them about the decision. As per law, the authority is bound to make decisions within 90 days after formal submission of an application for the land development. Once the land development plan has been approved with or without conditions based on the submitted documentations, the applicant has to strictly follow that plan. Part IV, Article 31(1) of the Act, states "whenever plans have been submitted to the Authority on an application for permission to develop land and such permission has been granted, the development must be carried out in accordance with the plans and any conditions imposed by the Authority." Failure to comply may result in enforcement actions. Nonetheless, according to the law, the Head of the PPU may approve minor variations in the plan and at some point, if the developer finds it difficult to implement the plan, then they may formally request changes to the plan. However, the Authority may or may not approve such amendments. According to the law, any disputes between developer and Authority relating to the land development will be settled through Physical Planning Appeal Tribunal.

The design of infrastructure is limited by the lack of resources for soil testing. There is a materials laboratory but only limited analysis is possible here. More complex analysis must go to the Caribbean Industrial Research Institute (CARIRI) in Trinidad and Tobago to make use of the available equipment and resources there. The ability to perform geotechnical analyses is also limited. Adequate runoff information does not exist. Rainfall data is only collected at sufficient precision for agricultural purposes and not for engineering purposes. There are rainfall stations at about 10 locations over the country but these record only daily rates.

Disaster risk management in Grenada

Grenada's vulnerability is particularly high due to its size, fragile economy, growing poverty, and limited capacity in addressing and coping with the impacts of any major hazard event. The government of Grenada has established the National Disaster Management Agency (NaDMA) with a primary responsibility of coordinating all disaster related activities in the country. There is a powerful National Emergency Advisory Council (NEAC), headed by the Prime Minister, responsible for giving direction and control and the development of policies. At the local level, there are 17 District Disaster Management Committees (DDMC) with the primary responsibility of disaster preparedness and response (NaDMA, 2014). NaDMA oversees and coordinates the operations of DDMCs.

Disaster risk management (DRM) in Grenada is a reactive and committee driven programme with no specific legislation. The national policy does not mandate DRM as a development objective (GFDRR, 2010). In 2003, the Caribbean Development Bank (CDB) and the Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency (CDEMA) produced the National Hazard Mitigation Policy for Grenada. It was emphasized that there was need to mainstream disaster risk reduction into national development planning and decision making as a crucial strategy towards vulnerability reduction. It stressed upon more proactive approaches to risk reduction (Linus, 2003). In 2006, a national hazard mitigation plan was developed through collaborative efforts of CDEMA and CDB under Caribbean Hazard Mitigation Capacity Building Programme (CHAMP) and Disaster Mitigation Facility for the Caribbean (DMFC) respectively (JECO Caribbean Inc., 2006). In 2011, NaDMA revised its National Disaster Management Plan (NDMP). However, none of these documents has any legal status. They are draft documents waiting for formal approval by the Assembly.

Status of hazard and risk information in Grenada

In Grenada there is no specific organisation that is responsible for undertaking hazard assessments and producing hazard and risk information. However, there are many government agencies that have GIS installed, such as the PPU, and the Land Use Division. These agencies have been involved in many hazard mapping exercises and received basic knowledge and training through external consultants under various hazard mitigation and response projects. There are still insufficient resources and capacity to undertake any risk assessment exercise independently without external technical support. There are a number of hazard maps produced for different hazards by the external consultants under various sponsored projects. Most of these maps are produced using qualitative mapping methods. These maps either cover the entire country or specific parts that are susceptible to a specific hazard. Table 3 lists an overview of available hazard maps in the country. This list provides information on the hazard for which the map was produced, scale, and the respective consultant who produced these maps. These maps are not easily accessible and some may be lost, because there is no centralised system in the country for storage and maintenance of geo-spatial data. Some of these maps were not produced in collaboration with the planning unit. However, some government departments share their data with other organisations particularly when staff have strong interpersonal relationships.

Table 3. Hazard Maps of Grenada

|

Type |

Purpose/ Description |

Coverage |

Scale |

Date produced |

Author/ Consultant |

Source of this information |

|

Multiple hazards |

To identify areas prone to natural hazards and recommend mitigation measures |

Towns of St. George's, Gouyave, Victoria Sauteurs, Grenville, Tivoli, St. Paul, St. David Parish, |

1:25, 000 |

June 1988 |

Vivian Bacarreza |

(CDERA, 2003d) |

|

Grenada erosion hazard map (draft) |

100 year return period hurricane event. Island-wide coastal erosion hazard map |

Island wide |

1:25, 000 |

October 2006 |

JECO Caribbean Inc |

(JECO Caribbean Inc., 2006) |

|

Grand Anse erosion hazard map (draft) |

100 year return period hurricane event.

|

Grand Anse |

1:10, 000 |

October 2006 |

JECO Caribbean Inc |

(JECO Caribbean Inc., 2006) |

|

Landslide hazard map |

Prepared as part of national hazard mitigation plan |

Island-wide (not including adjacent Islands) |

1:25, 000 |

October 2006 |

JECO Caribbean Inc |

(JECO Caribbean Inc., 2006) |

|

Landslide hazard map |

Prepared as part of national hazard mitigation plan |

Florida |

1:10, 000 |

October 2006 |

JECO Caribbean Inc |

(JECO Caribbean Inc., 2006) |

|

Flood hazard map |

Prepared as part of national hazard mitigation plan |

Island-wide (not including adjacent Islands) |

1:25, 000 |

October 2006 |

JECO Caribbean Inc |

(JECO Caribbean Inc., 2006) |

|

Flood hazard map |

Prepared as part of national hazard mitigation plan |

St John's river |

|

October 2006 |

JECO Caribbean Inc |

(JECO Caribbean Inc., 2006) |

|

Integrated Volcanic Hazard Zones- Based on Eruption of Mt. St. Catherine |

Prepared as part of national hazard mitigation plan |

Mt. St. Catherine area |

1:25, 000 |

October 2006 |

JECO Caribbean Inc |

(JECO Caribbean Inc., 2006) |

|

Kick em Jenny volcanic hazard zones |

|

Kick em Jenny area |

1:10,000 |

|

|

|

|

National level Flood map |

Under the CHARIM project |

Grenada (main Island) |

|

February 2015 |

ITC |

ITC |

|

Local level flood maps |

Under the CHARIM project and part of an MSc thesis |

St John's and Gouyave river catchments |

|

February 2015 |

Aris |

ITC |

Inclusion of disaster risk management in physical planning policies and development work

Although, there is no specific law which makes mandatory the use of hazard and risk information in the physical planning in Grenada, there is provision in the planning process itself for conducting such studies for making informed decisions. However, as mentioned earlier, there is no specific organisation in the country that has the mandate to produce such information and the planning unit has limited capacity to work independently on such studies. Therefore, the planning unit has to rely on maps produced by external consultants under specific projects and these products may not necessarily serve their purpose completely. This often leads to the exclusion of consideration about hazard in the development work. The PPU has access to some of these maps listed at Table 3 to be utilized for planning purposes. The planning unit uses these maps in a rudimentary fashion, particularly the Island-wide landslide and flood maps. The maps are super-imposed on parcel maps for identifying parcels that are at potential risk of flooding or landslides. In addition, the hazard maps have also been used for local area plan development of the Greater Grenville area.

For land development control, there are specific setback regulations concerning development in the coastal zone. These regulations are to ensure human safety and to protect development from storm surges, tsunami and other related coastal hazards, besides protecting sensitive coastal environment. It is stated in the Land Development Regulations section 17 that "the Authority shall not authorise any development closer than 165 feet (50 m) from the high water mark or on lands less than 10 feet (3 m) above mean sea level, whichever is applicable."

The National Physical Development Plan, which is an approved framework for physical development for the country, illustrates clear policy on risk management and emphasizes preventive and mitigation measures to protect the population and development work from natural hazards and the impacts of climate change (PPU, 2003). The policy states that the planning authority should:

- Institute appropriate disaster mitigation and preparedness measures.

- Integrate vulnerability reduction and risk avoidance measures of climate change adaptation into the development planning process

The subsequent policy implementation activities are defined in the NPDP and include the responsibilities to:

- Assess the nature and threat of current hazards and formulate appropriate hazard maps to guide development.

- Formulate and enforce land use requirements and building construction standards for disaster mitigation.

- Institute disaster preparedness measures and provisions for emergency management.

- Formulate vulnerability reduction and risk avoidance measures and the integration of such measures into the planning process.

- Integrate vulnerability and risk avoidance measures into the planning process

The National Strategic Development Plan (NSDP), which was prepared by the Agency for Reconstruction and Development (ARD) in 2007, is a document approved by the government that recognises the significance of environmental and physical development considerations for national development. The NSDP suggested the full implementation of NPDP including the items points mentioned in the preceding list, and mainstreaming disaster risk reduction and integration of environmental issues in the planning and development interventions.

Inclusion of hazard and risk information in local development planning: Case study of greater Grenville local area plan

The greater Grenville local area plan was prepared as an elaboration of the National Physical Development Plan. The town of Grenville, which is the second main town in Grenada, is located on the east coast within the Saint Andrew parish. This town needed regeneration to enhance its status as the regional hub of services for the east cost of the main Island. A development plan for the town was prepared, taking into consideration its regional significance. There were 7 goals and one of the main goals was to enhance protection of the environment, this includes; storm water management and drainage, hazard mitigation (landslides and flooding), water and sewer services, coastal erosion, wildlife, environmentally sensitive areas and national heritage, and litter abatement and cleanliness. An integrated planning process was adopted following guidelines outlined in the Act. The greater Grenville local area planning process focused on short-term and long term development opportunities for implementation with an overall strategy of identifying urgent needs and concentrating on solutions that can realistically be implemented.

The Grenville area is vulnerable to flooding, landslides, and storm surge. The area has been affected a number of times due to flooding. In November 2011, flooding badly affected the town and surrounding areas. A study was conducted in 2007 to identify flooding problems in the Grenville area. There were major issues related to the existing storm water management system; including maintenance, disrepair, and capacity. The drainage analysis study identified key findings and observations related to flooding in the area and suggested several remedial measures including adoption of appropriate storm water management technologies and planning strategies. The study also indicated that the town of Grenville is under threat from two sides: from the rising waters and storm surge and cumulative effects of run-off from agriculture and residential development upstream (PPU, 2007). Much of the downtown area of Grenville is less than 1.5 metres above sea level and according to a study on Grenada's coastal vulnerability (Moore & Charles, 2002), this indicates that there will be significant damage in the north-east area including Grenville due to sea level rise and effects of storm surge. Based on different combined scenarios of storm surge and sea level rise (up to 2100), it is concluded that there will be a significant impact on homes, business, and infrastructure. The majority of the beaches will have disappeared.

The main issues related to hazard mitigation and suggested remedial approaches for the greater Grenville local area plan (PPU, 2007) include the need for:

- Protection of environmental significance and biodiversity

- Protection against erosion: Certain coastal regions in the Plan Area have experienced erosion. At some locations the erosion width is more than 70 metres. These are the sites of significant sand mining. Enforcement against illegal sand mining must be in place to avoid coastal erosion. Additional measures includes restoring mangroves for soil stability. In other erosion prone areas commercial development along the water should adhere to increased setbacks and have suitable foundation to raise structures to an acceptable level of protection from storm surge.

- Protection against landslides: Parts of Plan Area are susceptible to landslides. In these areas no further development should be allowed in medium to high hazard areas. Restriction on any further development in these areas would limit any potential loss. However, updating of data and monitoring of the conditions is important. These measures should be complemented with public awareness and education on landslide issues.

- Protection against inland flooding: Parts of the Plan Area are susceptible to flooding. Moreover, the projected storm surge data for 2020 levels indicate that Grenville town and other areas in the Plan Area are subject to storm surge flooding. Development restrictions on areas identified as medium to high risk of flooding would limit any potential damage on these lands. Environmental initiatives, public awareness and education of local people and constant monitoring of these areas would ultimately reduce property damage.

Appropriate measures for storm water management in the Plan Area:

- Minimize storm water run-off from new and existing development by adopting storm water management approaches to accommodate increased run-off. This may include a combination of on-site storm water management (e.g. roof top, parking lot storage) remediation, conveyance controls, and detention/retention facilities.

- Review development approval procedures "“ review of approval procedures for development at the subdivision and development permit stage; this may involve existing by-laws, regulations, and storm water management design guidelines.

- Development of watershed management plan "“ eliminate increase in natural run-off for severe storm events e.g. 25 to 100 years due to new development, direct future development away from flood prone areas.

- Minimizing soil erosion, sedimentation and mass wasting due to soil failure

- Encouraging the natural recharge of water table without jeopardizing soil stability

- Adopting a zero run-off concept "“ there should be no net increase in storm water discharge from a site due to development

- Reviewing and adopting storm water management control systems

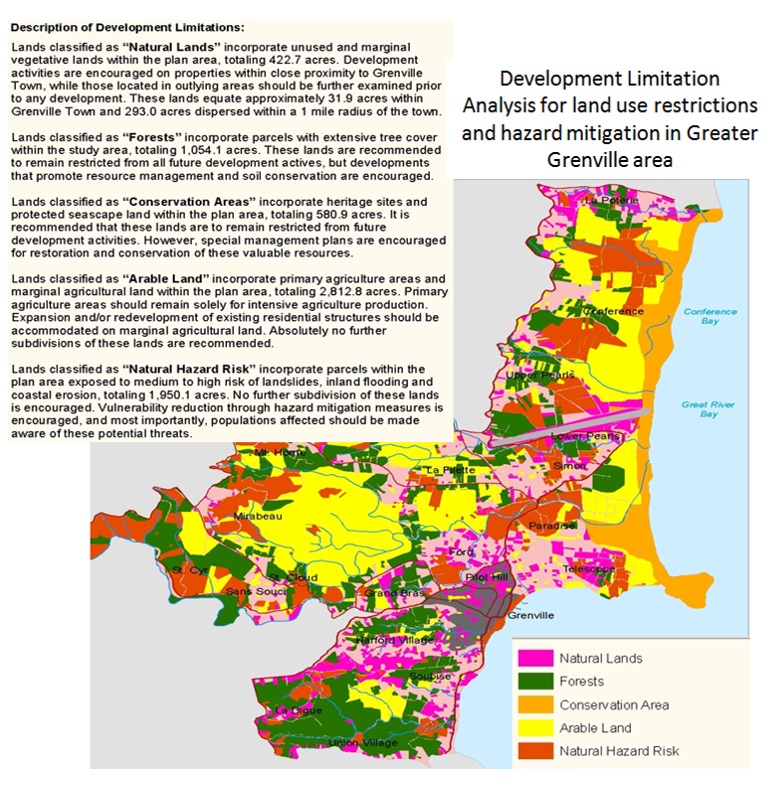

- Development limitation map: A development limitation map (figure 1) was produced by integrating all the mentioned hazards (flood, landslides and erosion) together with other land uses and included in the Grenville plan. This map is classified into 5 zones; namely Natural lands, Forest, Conservation area, Arable land, and Natural hazard risk. The natural lands, land use include unused and marginal vegetated lands Development activities allowed close to the town area

Figure 1: Development limitation map produced for greater Grenville area, East of Grenada (PPU Grenada, 2007)

Land designated as being for forested land use is not allowed to be developed on except for those development activities which promote resource management and soil conservation. The conservation areas are heritage sites and protected seascape land. No development is recommended here except restoration and conservation of these resources. Arable land is the primary agriculture areas. The land is dedicated for agriculture purposes and no sub-division is permitted for any other development work. Finally, the natural hazard risk areas are identified as possessing medium to high susceptible to landslides, inland flooding, and coastal erosion. No development is encouraged other than hazard mitigation works. Public education and awareness is considered to be important for its implementation.

- Zoning: Establishment of system of zoning. A zoning permit will be required to ensure compliance with the land uses and standards contained within individual zones. However, this concept is recommended as a long term goal due to challenges related to regulations and land tenure ownership.

References

- CDERA. (2003d). Staus of hazard maps vulnerability assessments and digital maps: Grenada country report (p. 11).

- Cooper, V., & Opadeyi, J. (2006a). Flood hazard mapping of Grenada (p. 35).

- ECLAC. (2005). Grenada: A gender impact assessment of Hurricane Ivan - Making the invisible visible (p. 53).

- Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR). (2010b). Disaster risk management in Latin America and the Caribbean region"¯: GFDRR country notes (Grenada) (p. 12).

- Grenada, G. of. Physical Planning and Development Control Act 2002 (2002). Saint Georges, Grenada: Physical Planning Unit, Grenada

- JECO Caribbean Inc. (2006). Grenada: National hazard mitigation plan (p. 95).

- Leisa, P. (2011). Gender and disaster risk reduction: An overview Caribbean (case study Grenada). Retrieved January 24, 2015, from http://www.slideshare.net/lperch2000/gender-and-disaster-risk-reduction-ifrc-caribbean

- Linus, T. S. (2003). Grenada national hazard mitigation policy (p. 20).

- Moore, R., & Charles, L. (2002). Grenada's coastal vulnerability and risk assessment. Belize. Retrieved from http://www.caribbeanclimate.bz

- Niles, Edward. 2013. Grenada, Carriacou and Petite Martinique Land Policy Issues Paper. Report prepared for The Social and Sustainable Development Division (SSDD) of the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS), Morne Fortune, Castries, Saint Lucia.

- Physical Planning Unit. National Physical Devlopment Plan (2003). Grenada: Physical Planning Unit, Grenada.

- Physical Planning Unit. Greater Grenville local area plan (2007). Grenada.

- Reliefweb. (2004). Grenada Hurricane Ivan Flash Appeal Oct 2004 - Mar 2005 - Grenada | ReliefWeb. Retrieved February 04, 2015, from http://reliefweb.int/report/grenada/grenada-hurricane-ivan-flash-appeal-oct-2004-mar-2005

- The University of the West Indies. (2011). Seismic Research Centre. Retrieved November 16, 2014, from http://www.uwiseismic.com/Maps.aspx

- Tony, G. (n.d.). Grenada: Making homes for the elderly safer following back-to-back hurricanes. Hospitals safe from disasters: reduce risk, protect health facilities, save lives. Retrieved January 26, 2015, from http://safehospitals.info/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=118%3Agrenada-

- World Bank. (2004). Grenada preliminary assessment of damages of Hurricane Iva (p. 12).

- World Bank. (2005). Grenada: A nation rebuilding - An assessment of reconstruction and economic recovery one year after Hurricane Ivan (p. 70). Retrieved from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTLACREGTOPHAZMAN/Resources/grenanda_rebuilding.pdf